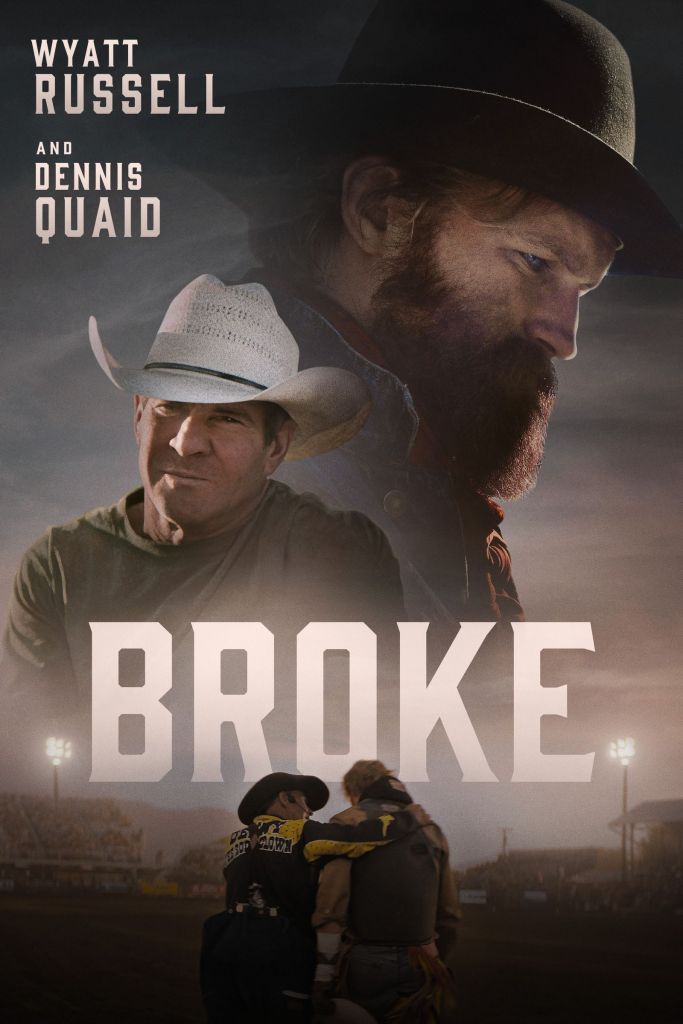

Where do you go when the bronco ride is over? That’s a question True Brandywine (Wyatt Russell) refuses to confront. He’s a bareback bronc rider who lives for the moment he can get on the horse and just let everything go. In those moments, he’s focused. Outside of those moments, he’s aimless, living with his parents George (Dennis Quaid), Kathy (Mary McDonnell), and younger brother Caleb (Johnny Berchtold). George relentlessly presses his older son about his plans, encouraging him to join the military and begin building something substantial. True remains reluctant to consider anything but bronc riding.

A chance meeting introduces Ali (Auden Thornton) into his life, and she’s immediately revealed to be the type of person that provides True the love and partnership he’s unconsciously searching for, accepting him for who he is while knowing there’s much more he can accomplish beyond his chosen occupation. Yet the draw remains enticing to True, even at the expense of rapidly decaying health physically, mentally, and emotionally. He has no choice but to confront those realities when he’s trapped alone in a snowstorm in a fight for survival.

Beginning in media res and almost horror-like is not the way I and probably most people expected Broke to begin. It’s an interesting choice, and so too is the way Broke’s story is predominantly told via flashbacks. Takes some time getting used to and the past “part” of the story is more gripping than the current part, but the decision generally proves to be a sound one allowing the movie to incrementally build its emotional core.

After partnering with director brother William Eubank on writing and set construction across films, the younger Carlyle gets his opportunity to direct one for the first time. It doesn’t take too long too to see the passion and authenticity he has and brings into this world, shooting in Montana across the seasons and using real rodeos and the energy imbued in those to intersplice the action scenes. Editing is as much of a strength here as directing is, as the work of Glenn Garland is paramount to understanding the sublime aspects, but mostly violent and taxing physical demands of bronc riding.

The traditional western is rarely profitable today in Hollywood nor inspires mass interest in audiences, but contemporary westerns have been a thing for a while, and the themes found in Broke are ones that can be found in many films. A prominent one here is addiction, not only in the obvious sense, but the addiction we as humans might have to our dreams, our self-identity, or even to bucking authority and responsibility. Seeing this play out over the course of 103 minutes is the most compelling piece of the feature. Where Eubank’s film wanes at times is in the survival areas, seeing True try to stay warm, avoid danger, etc. While this part is more than competently made and doesn’t consist of the bulk of the runtime, I found myself wanting to get back to the past as quickly as possible.

Broke’s character depth gives an opportunity for its lead star, Russell, to showcase his toolbag in ways last year’s Night Swim and the recent Thunderbolts* does not. At many moments, he is True, disappearing into the role and occupation effortlessly as a three dimensional character. Quaid is a steady hand for nearly every movie, and Thornton, not someone I was too familiar with, manages to impress in a part that isn’t meaty but still asks a lot from a pathos perspective.

Broke is destined to be forgotten at best, undiscovered at worst amid the current wide releases and even other streaming popular fare, and it shouldn’t be, Set against the backdrop of Big Sky country, Carlyle Eubank’s non-linear directorial debut about the struggle of holding on to what defines us is a patient and powerful feature driven by the emotional range of Wyatt Russell.

B

Photo credits are courtesy of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.